A Church Service, a Hymn to Human Need (Dr. Nikolaos Koios, Content Coach of Pemptousia)

7 Δεκεμβρίου 2017

Hymnography is the jewel in the crown of Church Literature in Orthodoxy. A variety of metres, a combination of poetry and prose, all invested with the musical riches of the eight tones, narrate the drama of the human person in our effort to trace the invisible and enter into communion with the Uncreated.

Even so, there are some services which really do stand out, where the inspiration of the poet is apparent, from the first troparia of Small Vespers to the doxastiko at Lauds at the end of Matins. The quill flows effortlessly and combines words and music in a pulsation of art and meaning, outside the ordinary yet so close to everyday human reality.

One such service is that of Saint Nicholas, Bishop of Myra. If you look at the service book (Minaio) for December from a hymnographical and literary point of view, it can be compared in its beauty and variety only with that of Christmas itself. The ascetic second tone and the cicada-like melody of the second plagal are interwoven with the joyful and sprightly first tone and the resurrectional and intercessionary plagal first. ‘Wearing a crown, in the steps of Christ…’ [1]. ‘With unendowed tongue and lips, a short hymn of praise and intercession…’[2].

What is it that moved the hymnographer, in essence, to herald the mystery of the incarnation of the Divine Word, which we’ll be celebrating in a few days, through the life of a saint, in this case Saint Nicholas?

The composer of the service adeptly provides us with the answer:

‘divine joy of those in sorrow,

‘divine joy of those in sorrow,

defender of the betrayed, champion of those in danger,

greatest shield of widows,

avenger of the oppressed,

enricher of the poor,

protector of sinners,

helmsman of those at sea,

doctor of the sick,

guide of those who have strayed,

companion to travellers’.

When we sing and read the service of Saint Nicholas, we direct our attention to the whole of human pain: the injustice that suffocates the betrayed, the dignity torn to shreds, the abandonment of orphans, the loneliness of widowhood, the exploitation of the weak, the struggle to make a living in adverse conditions, the helplessness in the face of natural disasters, the canker which eats away the human person, the vacillation when faced by difficult choices.

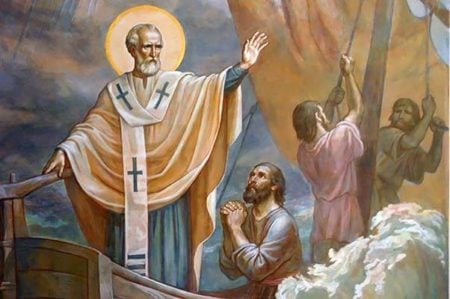

There’s perhaps no other saint who’s so much ‘in the flesh’ and so accommodating as Saint Nicholas. Although he was educated, was a bishop who took part in the 1st Ecumenical Synod, and expressed his indignation at the false doctrine of Arius, he left behind no written texts in which he might have recorded his spirit and faith. He preferred to ‘write’ a book, as it were, with his own life. To reach out to those in need. To the people whom Divine Providence had sent him. He didn’t serve some sort of abstract, humanitarian idea. With might and main, he served those who were in need at a particular time and place, wherever and whenever he might be of help. From an early age, he was the support of the poor. This doesn’t mean, however, that he ignored injustice towards representatives of the ruling class as it was then, such as the three generals who were slandered. Through his prayers, he saved a ship which was being buffeted by a storm and resurrected a young sailor who’d been crushed when falling from a mast. He didn’t hesitate to spend large amounts of money to rescue the dignity and integrity of the young daughters of a father who’d once been rich but had since become financially bankrupt.

In the hymnographical texts, he’s presented not as a persecutor or chastiser of sinners, but as their protector [3]. In imitation of Him Who saved the adulteress from stoning, the harlot with the myrrh from revilement and Zacchaeus the Publican from rejection.

Towards the end of his life here on earth, the late Elder Yelasios Simonopetritis related a story which we heard and which we’ve dredged up from our memory some thirty years later. Father Yelsasios held in great honour Saint Cassian the Roman, whose feast day falls on February 29 and therefore occurs only once every four years. The elder told this little story in the form of an anecdote. Saint Cassian complained before the heavenly throne because his feast was celebrated only once in four years, while some others have more than one feast a year. So God ordered the angels to fetch Nicholas of Myra. They searched high and low, but then Nicholas appeared before the heavenly throne, bedraggled from battling against heavy seas. When asked: ‘Where were you Nicholas?’, he answered: ‘There were some people in danger, in a storm, and they needed me’. Turning to Cassian, God said: ‘Now do you understand why Nicholas is honoured not just two or three times a year, but every week?’

In our ecclesiastical and Christian life, there’s often a temptation to over-emphasize the spiritual and to undervalue the corporeal and social elements of human life. This over-emphasis creates problems both in morality and dogma. In little more than a couple of weeks we’ll be celebrating the incarnation of the Word, the separation of human history into before Christ and after Christ. Christ the Word put on our own flesh and became the same as us in everything except sin. He took on the whole of our humanity, history, culture, pain, anxieties, expectations and our need to be liberated from the bonds of death. He didn’t respond only to the theological questions asked by Nicodemus [4], but also to the anguished cry of the disregarded Canaanite woman: ‘My daughter is tormented by a demon. Have mercy on me’ [5].

Saint Nicholas hastened to meet everyday needs, things which many of us overlook as regards our neighbour, supposedly because we’re seeking a higher spirituality. By his practical support, inspired by the Gospel, for the oppressed and fallen, he became ‘full of the beauty of things unseen’ [6], he understood the dread glory and was called the saint of saints, even all-holy [7], and he declares to us the sublime words of everlasting contemplation. The wrenching of his heart on behalf of people in need is grafted on to eternity and his temporary and earthly care of those in sorrow is transformed charismatically into celestial and eternal glory.

He teaches those of us who are concerned with theology that the quest for sublime meaning bears fruit through small, everyday things. Through our embrace of those who have gone astray and have sinned, who are often burdensome to us. Through our concern and practical care for those in need. Through our humble and selfless boldness in the face of injustice.

Happy feast day, with the prayers of all-holy Saint Nicholas.