The Reception of the Lord: the feast of freedom (George Mantzarides, Professor Emeritus of the Theological School of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki)

3 Φεβρουαρίου 2018

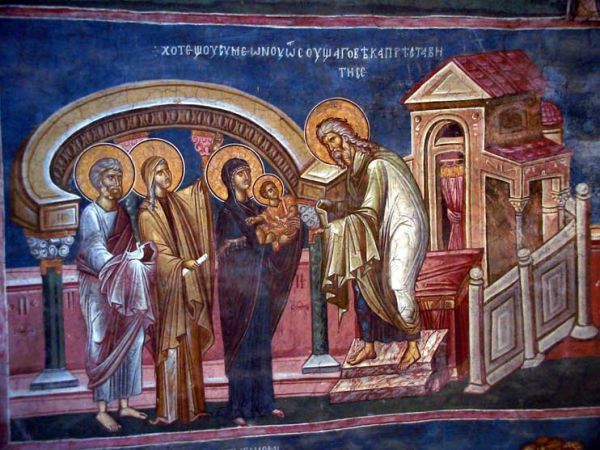

In one of the hymns at the Vespers of the Reception of the Lord, the words ‘Now, Lord, you let your servant depart in peace’ which were addressed to God by the righteous Symeon when he took Christ into his arms, are rendered by ‘Now I am released, for I have seen my saviour’[1]. In the person of the infant he was holding, Symeon saw his peace and release.

The feeling of peace is the sense of God’s proximity. Peace brings people closer to God and to each other. This is clear from the etymology of the word which goes back, through Latin, to a Primitive Indo-European root, *pag, meaning ‘to bind together’, as in the related word ‘pact’. In particular, God-given peace, the peace of Christ was given to the disciples as a parting gift, at the completion of Christ’s incarnate ministry, through his words: ‘I give you my peace’[2].

As a fruit of the Holy Spirit, Christian peace is directly linked to love and joy: ‘for the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace…’[3]. It’s linked, in other words, to our happiness and liberation from our confining limits. And in the dismissal hymn for the feast, Christ is called the ‘liberator of our souls’, Who grants us the resurrection.

Symeon the righteous was at the end of his life on earth. He had no further prospect of extended years. And the place where his trembling limbs could move was also limited. He was bound, almost immobile, as regards place and time. How could he say he’d been liberated?

Freedom presupposes an unleashing from any restrictive bond. It offers the chance of expanding and moving in both place and time. Even more, it provides the opportunity to overcome space and time. What sort of freedom can somebody have when they’re about to die? How free can somebody be when their movement’s restricted? This is how Symeon lived. This was his physical condition.

Despite this, Symeon had something very important within himself. He had a hope, or, to be more exact, an expectation which would be fulfilled within the bounds of his earthly life. He had God’s promise that, before he died, he’d see the Messiah: ‘It had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit that he would not see death before he had seen the Lord’s Messiah’[4]. This is who he was waiting for.

Expectation of the Messiah gave meaning and content to the life of righteous Symeon. And the fulfilment of this expectation made him ask the Lord God for his dismissal, his death. He wasn’t awaiting anything else. He’d seen what he’d been waiting for. There’d be no sense in any further extension of his earthly life. This is why he asked to be dismissed.

Dismissal is discharge from all authority. It’s the release from certain bonds. But dismissal per se also has a negative connotation. It’s a rupture. And rupture involves pain. Much more so the pain that’s connected with death. ‘I lament and weep when I contemplate death’. ‘What a struggle the soul has, separated from the body’. But Symeon neither mourns nor sees any struggle before him. He’s dismissed in peace.

Nobody’s happy or at peace if they’re dismissed from their post against their will. They are, however, if the dismissal is by mutual consent, if it’s linked to the completion of the ‘end’, that is of the aim of a particular task and the undertaking of a better or higher one.

When the exit from this fleeting life is linked to the entry into immortal life, then death has a positive connotation. It becomes a celebration. This is why the deaths of the Saints of the Church are celebrated with feasts. Saint Paul addresses the faithful with a triple exhortation: ‘Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you [5]. This means that joy, prayer and thanksgiving are held to be an indivisible, triune act.

Righteous Symeon calls the dismissal he was awaiting ‘peaceful’, because it fulfilled the promise God had given him regarding the salvation of all peoples. His words reveal a man with a heart of world-wide dimensions. They show that he embraced all peoples, was at peace with everyone and founded this peace, as the peace he had within himself, on peace with God.

The cause of this experience of Symeon’s, as the Vespers hymn makes clear, is that he Whom he’s embracing is ‘God the Word from God, incarnate for us’. The incarnate God the Word unites us with God, brings boundless eternity into the defunct world and transforms corruption and mortality into incorruption and immortality.

These events don’t have any theogenic meaning. They don’t refer to God but to us people. God becomes incarnate in order to save human nature. He becomes a person in order to make us gods. He is God by nature and makes us gods by Grace. He transmits to us His uncreated Grace, His life without end. He makes us sharers and participants in His love and His bliss.