Thanksgiving and Gratitude (Ioannis Karavidopoulos, Professor of the School of Thelogy of the University of Thessaloniki)

21 Ιανουαρίου 2019

Imagine for a moment how frightening it would feel to be cut off from all other people, without any chance of contacting or encountering anyone else, while at the same time having a body which was sick and continuously deteriorating as a result of a contagious disease. Add to that the permanent disdain of people who believed that the disease we had was a punishment for our sinful life. Then suddenly along comes someone who approaches us, ignoring the dangers, trampling on the prevailing social prejudices, demonstrating clearly and fearlessly His love for us. Wouldn’t we be endlessly grateful to Him?

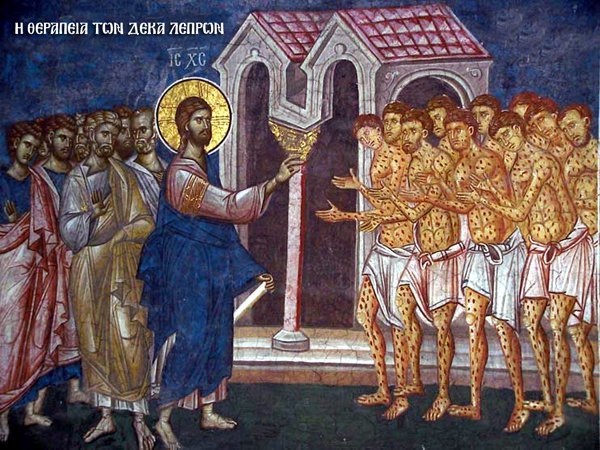

Such was the case, presented in Saint Luke’s Gospel narrative, of the ten tragic lepers who were touched by Christ’s saving grace and curative power. God’s love, which became incarnate in the world and was revealed in the life and death of Christ, isn’t restricted to the few, the chosen, to His own familiar friends. It extends to all, even- or rather, especially- to those whom the ‘serious’ and ‘pious’ of each era consider to be tainted and sinners. It knows no social, political or religious restrictions. It was expressed in the case of the narrative of the ten people united in the pain of a degenerative disease. Jesus meets them and talks to them, overcoming the Law of Moses which forbids any contact with lepers. One of them was even a Samaritan, that is a foreigner.

And yet it’s the attitude of the latter that makes an impression on us and is underlined by the Evangelist. Nine of those who were cured, full of the joy of life and of meeting their friends and relations, of seeing their body strong and cleansed again, forgot to express their gratitude to Christ, their benefactor.

They were typical of those who, after exhausting all human powers, in their pain and sorrow call upon God as being their last refuge in sickness, yet who then – in their joy – forget that He was indeed their first friend in health and joy.

It’s certain that the anguished cries of help that are addressed to God on a daily basis far outnumber the prayers of thanksgiving and gratitude.

There are plenty of things in life that we take for granted, without feeling any obligation to anyone else for these everyday gifts. Our self-sufficiency and self-confidence leave no room for gratitude to God, our Benefactor. It’s difficult for our lips to say ‘Thank you’, while it’s very easy, almost spontaneous, to express cries of entreaty for help in times of need. And this is where something absolutely typical occurs: once the time of need has passed, we don’t just forget our moment of frailty and feel embarrassed about it, but, with a show of bombast, we even try to counterbalance the weakness we showed.

This is an entirely human stance and reveals how trapped we are within the defensive walls of our egotistical thinking regarding the self. And yet, the saving love of God surrounds us on a daily basis. Christ’s Cross isn’t merely the culmination of a series of redemptive actions that God has performed for us, His creatures, but it’s also the beginning of the boundless gifts He showers upon humankind. The most important of these is the triumph over the fear of death and the blossoming of the hope of the resurrection.

When the stench of death threatens to transform everything around us into a charnel-house, isn’t the bourgeoning of the hope of a new life, without pain, without sorrow and without the fear of death a fundamental reason for being grateful to God? Immersion in ourselves, Pharisaical self-sufficiency and seemingly dynamic self-confidence, all bear the stamp of the threat of death. Opening our heart to God is our response to His infinite gifts, the gift of life which He’s generously offered us. It’s our ‘Thank you’ to Him. It’s an expression of thanks which should certainly be accompanied by behaviour appropriate to such a divine gift. In the Gospel narrative, the expression of thanks to Jesus came from a Samaritan, a foreigner, who was disdained by pure Jews. The pain of sickness united the ten lepers; at the end of the account, the gratitude of one, the Samaritan, drew the praise of Christ and His recognition of that man’s faith.