There are Saints and Fathers of the Church Today (Nikos I. Nikolaidis, Professor)

16 Ιανουαρίου 2021

In former times, professors of Patristics, even Orthodox theologians, considered that there were no more Fathers in the Church after the 8th century. In other words, they closed the borders of Patristics, refusing to accept there were other Fathers after John the Damascan.

This view of the matter, even on the part of Orthodox professors, was heavily influenced by the theology of the Protestants, who, as is well known, rejected the existence of saints, referring to them mockingly. Protestants also doubted or rather, in practice, played down the position and role of the Fathers of the Church. One outcome of this is that there was no involvement with Orthodox ecclesiastical literature written after the 8th century and this clear marginalization and lack of appreciation even included that giant of Hesychasm, Saint Gregory Palamas*.

Fortunately, this erroneous view of the Fathers has been revised and today Orthodox truth prevails: that the Church continues to produce and promote Saints and, indeed, Fathers all the time. And woe betide us were this not so. That is, if the Church stopped being a workshop producing Saints and Fathers, because in that case we, the faithful, would have to be concerned whether what we belonged to was the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church.

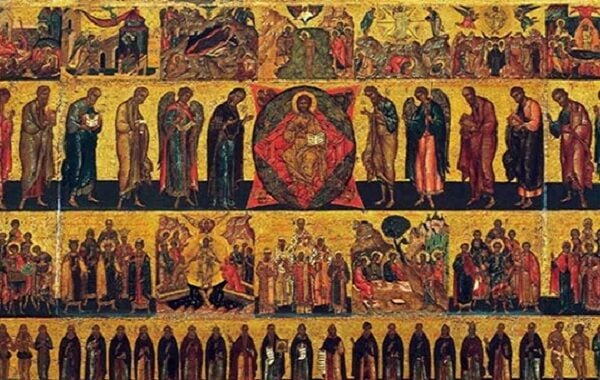

The Church is the Body of Christ and we are its members. Christ is the head of the Church and its Savior (Eph. 5, 23). So if the Church doesn’t beget Saints and Fathers in our own times, too, then it’s ‘sterile’ and is consequently null and void. But this isn’t the case, since the Church has presented a whole host of Saints and Fathers over the years. Outstanding proof of this in recent times are the ranks of the New Martyrs and our contemporary Saints.

What are Nikodimos the Athonite, the Kollyvades, Saints Nektarios, Silouan the Athonite and others? They’re certainly Saints and can claim to the title of Fathers of the Church, because, apart from their holy life and Orthodox outlook they have also bequeathed to us written works. Through their ministry they also presented us with various challenges, as the mouthpiece and voice of God to His people.

Besides these, there are also Iosif the Hesychast, Sophrony (Essex), Filotheos Zervakos, Gavriil Dionysiatis, Iakovos (Tsalikis), Païsios, Porfyrios and others who have already been established in the ranks of the Saints and the Synaxari of the Fathers, as far as the faithful are concerned, and this is what matters most. What remains is their official canonization and- why not?- recognition of them as Fathers of the Church.

What we’re saying is neither vacuous nor novel. We’re simply interpreting Orthodox ecclesiology and practice. The common conscience of the faithful members of the Church (clergy and laity) is the criterion for Orthodoxy and Orthopraxy as regards the Saints and Fathers of the Church.

The Saints and Fathers of the Church, as people who ‘have received the Holy Spirit’, as Saint Epifanios puts it, never act spontaneously or of their own accord, but, within the bounds of the times in which they live, they express the Orthodox tradition, ‘as this has been preserved from of old in all purity’. They do so without diminishing it and in accordance with the challenges of their times for the Church. In this way, the Church guides the people of God and accompanies them in the world, pointing the way to their destination in the end times, with the Saints and the Fathers as its mouthpiece and voice, especially when there is a ‘demand’, as Fotios the Great puts it. And the Church has never ceased to face a variety of ‘challenges’ and ‘demands’, because the devil envies it and aims to ‘sweep it away with the torrent’ (Rev. 12, 15).

*One reason for this, of course, is that until the 8th century, competent translations were available in Latin in the West. Thereafter, for geo-political reasons, knowledge of Greek declined, even among scholars, until it revived somewhat when first Thessaloniki and then Constantinople fell to the Turks in the 15th century, leading to a flight of educated men who were given posts in leading universities in the West in order to teach the language. In 1516, Erasmus produced a Greek/Latin New Testament (Instrument) which is admirable in many ways and had a huge impact, but is nevertheless often inaccurate. And, of course, Erasmus and others had Jerome’s 4th century Vulgate (itself a revision of the Vetus Latina) as a ‘crib’, if they were faced with a difficult passage. Thus it was that, for example, the King James English version of the Bible was basically translated from Latin rather than Greek, as is clear particularly from choice of vocabulary. What Professor Nikolaïdis says about the attitude of the West towards the Fathers is certainly true, but we should not ignore the fact that not many people could have understood texts by Saint Gregory Palamas, for example, as they would have been hampered in doing so by a lack of knowledge of either the actual language, or of Orthodox theology, or both. Naturally, there were exceptions to this, such as Barlaam the Calabrian, Gregory’s opponent, who was completely fluent in Greek and was fully acquainted with Orthodox theology, but these were, in the broader picture, few and far between [WJL].