The Early Centuries of the Greek Roman East (2)

29 Μαΐου 2009

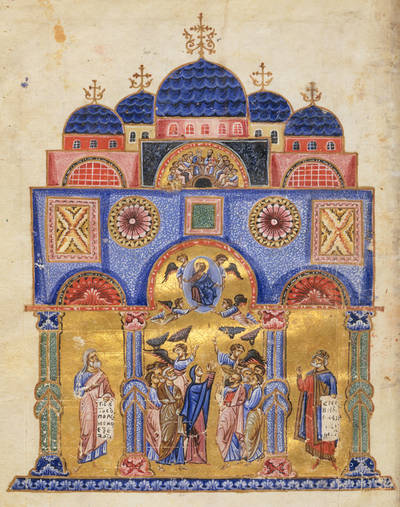

A page of a byzantine illuminated manuscript of the 12th century, depicting the Ascension of Christ and two prophets. Φύλλο από βυζαντινό εικονογραφημένο χειρόγραφο του 12ου αιώνος, που απεικονίζει την Ανάληψη του Χριστού και δύο προφήτες.

The Advancement of Architecture

The ruler as builder was one of the oldest ideals of a sovereign. Public buildings and other structures were, in principle, gifts to be used by the ruler’s subjects, but also monuments of the greatness of the ruler. Justinian strove hard to realize this ideal. The greatest buildings he erected or rebuilt were in Constantinople, the city which was now the embodiment of the civilization of the Eastern Roman Empire. Numerous magnificent and artistically beautiful structures were constructed or rebuilt during his reign. They included statues, churches and various other monuments. His crowning achievement was the building of St. Sophia, the Church of Holy Wisdom. This building was considered by many an architectural wonder of the middle ages, and is still standing strong today. Its design, size, artwork, name and its significance made it a building that symbolized the religious and philosophical epicenter of Constantinople and Byzantine civilization.

Even before he came to power, during his uncle’s reign, Justinian had already set about to rehabilitate and rebuild many churches in Constantinople and its suburbs. This work began mostly in a private capacity and reflected the piety which was to show itself further when Justinian became emperor. The chief church in this category was St. Accius, a Cappadocian soldier who had been executed at Byzantium in the early 300’s and was venerated as one of the leading martyrs who had suffered on the site of the future Constantinople. Six other churches were similarly rebuilt. One was St. Mocius. This was one of the most famous shrines in Constantinople. It was said to have been originally a temple of Zeus, which Constantine then converted into a church. Other churches included St. Plato, martyred at Ancyra, and St. Thyrsus, executed in Nicomedia in the same persecution. In the suburbs of Constantinople he rebuilt a church of the famous woman martyr, St. Thecla, who suffered in the first Christian century.

When Justinian came to the throne, he found many of the major public buildings and churches in dire need of repairs. His private undertakings were replaced by an official program to rebuild and construct churches throughout the whole empire. The reign of Justinian would have been incomplete if it had not brought with it some new monuments to the glory of the empire, and Justinian was eager to have a permanent literary record of his building achievements. To this end Justinian had at his disposal the famous Historian Procopius who wrote, at the Emperor’s command in the years 559-560, the famous panegyrical treatise “On the Buildings of the Emperor Justinian”. Far from being displays of megalomania, Justinian’s works constituted a well balanced plan. First, he wished to provide the people of the capital with much needed public buildings. Second, to create a new architectural setting for the institutions that represented the chief political and spiritual resources of the empire and its civilization. Justinian surpassed the work of Constantine, who up to that point had been the greatest builder among the Christian emperors of the Empire.

One of Justinian’s best known benefactions was the rebuilding of a hospital for the poor which had been constructed in the early days of Constantinople. Well outside Constantinople, at a place called Argyronium, on the shore of the Bosporus, there had been a free hospital for people with incurable decease’s. This hospital had been neglected until Justinian rebuilt it. Procopius tells us of three other hospitals reconstructed by the Justinian and the Empress Theodora, acting together.

Justinian also improved numerous other public works. For example. work was done for the water supply into the city. The most difficult problem was to maintain an adequate supply of water in the city year round. In the area of the Augustaeum, general repairs were undertaken of the colonnades which lined the main street leading from the Augustaeum to the palace of Constantine. The public bath of Zeuxippus was embellished. In Justinian’s day this bath,going back to the Greco-Roman days of Byzantium, was one of the show places of the city. It had a collection of eighty classical statues, which were described by poets and copied by various artists. In the suburbs a general program of development was carried out at Hebdomon, on the shore of the Sea of Marmara. A market place, public baths, and colonnades –some of the chief needs of municipal life in a city very much in contact with its classical roots– were built. As well, the emperor had an artificial Harbour built at Hebdomon which, along with the artificial harbours of Julian and Theodosius, provided refuge to ships in stormy weather.

Great as all these building operations were they still were small in comparison to Justinian’s churches. Every city of the eastern Roman Empire required an ample number of churches and it was only fitting that the capital should have more than usual. We have the names of 34 churches that the emperor built or rebuilt. Most were dedicated to many members of the celestial hierarchy and to a number of saints and martyrs. In addition to those churches he built or rebuilt as a private citizen, there are associated with the emperor. Most famous of these was St. Sophia (the Church of Holy Wisdom) rebuilt after a fire brought the old one down on January 13, 533. There was also St. Eirene (the church of the Peace of God); four churches to the Virgin Mary; One of St. Anna; four churches of the Archangel Michael, who had a special cult in Constantinople and was venerated as a wonder worker; a church of St. John the Baptist; one of all the Apostles and another of St. Peter and Paul; and churches of joint dedication to St. Sergius and St. Bacchus; to St. Priscus and St. Nikolaos. As well, other churches were built by Justinian for Panteleimon Tryphon, Ia, Zoe, and Lawrentius. This list also includes the Church of the Holy Apostles, replacing a building of Constantine the great. This church occupied a special place among churches in that it had been intended by Constantine the Great as a burial place of his dynasty, and a mausoleum had been built outside the apse of the church. Here lay the tomb of Constantine surrounded by members of his family and successors. By Justinian’s time the mausoleum had become full, and so Justinian constructed a new tomb near it for himself and his successors. As a result the church of the Holy Apostles was regarded as second in importance after St. Sophia.

Architecturally Justinian’s churches illustrate the final development of a design in church building which was to be typical of Greek Christianity. After the official recognition of Christianity, the first churches to be built were based mainly on the plans of the Roman public Basilicas. But slowly this fashion went out of style in the territory of the Eastern Roman Empire, in favour of the building of square or cruciform plan designed around a central dome. This design gave the church both liturgical function and a symbolical significance which were much more congenial than the basilica to the Greek religious mind. It was in churches of this design that Justinian’s architectural ambition reached its fullest realization, and set an example for future builders.

The church of this type was essentially either a square or a cross surmounted by a central dome. The structure below the dome might be conceived as a cube or a cross with equal arms which could be inscribed geometrically within the cube. Occasionally there might be a cross with lower member longer than the others. The octagonal plan was also developed. The dome stood alone over the center of the square, or over the intersection of the arms of the cross; or a great central dome might have been accompanied by smaller domes built over the arms of the cross. But it was in the central dome that the significance of this new design lay. The dome unified the whole structure of the church and brought all its areas and spaces together around one central focus. The Hemisphere of the dome, which rose above this central spot symbolized heaven. It was meant to be visible, at least partially, to all worshipers in the church and served to bind the entire congregation. The altar was usually placed in an apse in the east of the building, and in the square or cruciform plan, the congregation was closer to the altar than they had been in churches of the elongated basilica plan. In some buildings the altar stood under the central dome, giving an even greater feeling of unity to the congregation. The dome also created an impression of vast space, and gave the whole interior of the church a majesty and dignity which inspired a sense of inner peace and intellectual detachment. On the dome was usually painted a great portrait of Christ Pantocrator (Christ the allmighty). The architecture and imagery the dome conspired with one’s mind to give the illusion of bringing heaven to earth. In many ways the dome created the sensation of exposing a realm, the realm of the divine, to which we could look to for truth and holy wisdom. In this sense the design of the Byzantine church incorporated much of the imagery of the Platonic realm of absolute ideals, the ultimate of which was the Holy Wisdom of God.

The Church of St. Sophia

In none of the churches of Constantinople could the mind reach a greater sense of spiritual depth and nobility than in the so-called “Great Church” of St. Sophia. This was almost certainly Justinian’s greatest architectural achievement. It is very characteristic of the spiritual life in the Eastern Roman Empire in the days of Justinian, that the Emperor chose to build, as his own greatest church –which was also intended to be the greatest church in the world– a shrine dedicated to Christ as “Hagia Sophia” or Holy Wisdom in English. Christ, the Wisdom (Sophia) and Power( dynamis) of God, in St. Paul’s words, was a manifestation of the holy trinity, projecting the action of God from the realm of the divine to the world of man. It is by no means coincidence that the chief temples of Pagan Athens and Christian Constantinople were both dedicated to Wisdom. The Parthenon as the shrine of the Goddess Athena, Goddess of Wisdom, and Justinian’s Great Church both showed respect for “Sophia” which has always been one of the chief traits of the Greek mind. Christ as the Wisdom of God was a familiar idea to Greek Christianity; the Hymn of the Resurrection, sung during the Eucharist, invokes Christ as “the Wisdom and the Word and Power of God”. Near St. Sophia stood St. Eirene, representing the peace of God. Like St. Sophia, St. Eirene had been originally built by Constantine the Great. It is highly indicative of the Eastern Roman Empire’s connection with its Classical Greek roots, that when both St. Sophia and St. Eirene were burnt down and rebuilt, Wisdom was given first place.

Just as Justinian had found skilled legal scholars (Tribonian) to re codify the laws, as well as skilled generals to recapture lost lands (Belisarius), so too he was fortunate enough to have found two builders of the highest talents to build St. Sophia. They were Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Melitus. As well as builders they were also noted mathematicians, which was to be of basic importance in the accomplishing the task Justinian set for them. St. Sophia was built in the traditional Greco-Roman style, but it represented a design and scale never before attempted. The main area of the interior, designed for the services, was a great oval 250 by 107 feet; with side aisles, the main floor made almost a square, 250 by 220 feet. The nave was covered by a dome 107 feet in diameter, rising 180 feet high above the ground.

The design created the impression of a vast enclosed space. This was made possible by an intricate series of supports, all of which were arranged so as to lead the observers eye from the ground level up to the dome. At the east and west of the nave were hemicycles crowned by semi-domes, which provided some support for the superstructure. Each hemicycle was flanked and supported by two semicircular exedras carrying smaller semidomes. At the eastern end the hemicycle opened into the apse with its semi-dome. With rows of columns supporting the upper galleries on the north and south of the naive, and numbers of clear windows in the walls, in the semidomes, and around the base of the main dome, the supporting elements looked incredibly slender and light. The ring of forty-two arched windows placed close side by side at the springing of the main dome seemed almost to separate the dome itself from the main building. The historian Procopius in his accounts of St. Sophia tells us of the astonishing effect of these details. The weight of the upper part of the building appeared to be borne on terrifyingly inadequate supports, although it was very carefully braced. The dome itself, Procopius tells us, seemed not to rest upon solid masonry at all; instead it appeared to be suspended by a golden chain from heaven. The bold conception and design of the building were matched by the skill with which it was constructed. A structure of such size and plan were never again attempted in Constantinople.

As with the design and fabric of the building, its decoration was chosen to produce a transcendent spiritual effect. Typically in Greek-Orthodox churches, applied ornament was concentrated on the inside leaving the outside to show the mass of the structure and bring out its geometric patterns of curves and lines, which the Byzantine mind so greatly appreciated. The interior decoration was sumptuous but risked being gaudy. It contained a richness indicative of the prosperity of the empire as a whole. Paul the Silentiary, one of the members of Justinian’s court, wrote an elaborate description of the church in verse which shows what the magnificence of the decoration must have been like when St. Sophia was in its original state. Many lands, Paul tells us, sent their own characteristic marbles, each of with its distinct features; black stone from the Bosporus region, green marble from mainland Greece, polychrome stone from Phrygia, and porphyry from Egypt and yellow stone from Syria. The different stones were used in carefully planned combinations in the columns, in the pavement, and in the revetments of the walls.

Rising above was the main dome, showing the cross outlined against a background of gold mosaic. The semidomes were also finished in gold mosaic, and the pendentives beneath the dome were filled with mosaic figures of Seraphim, their wings like peacock feathers. Against the background of marbles and mosaics the church was filled with objects of shining metal, gold, silver, and brass. From the rim of the dome hung brass chains supporting innumerable oil lamps of silver, containing glass cups in which the burning wick floated in oil. Beside the side colonnades which separated the aisles from the nave hung other rows of silver lamps.

It was in the sanctuary that the precious metal was used to its fullest. The visitor would first see an iconostasis, the columnar screen which stood in front of the altar. The screen itself was made of silver plated with gold. Depicted on it were Christ, the virgin Mary and the apostles. At intervals in front of the screen were lamp stands shaped like trees, broad at the base, tapering at the top. In the center of the screen was the Cross Christ, brightly illuminated. The gates leading into the sanctuary bore the monogram of Justinian and the empress Theodora. Within the sanctuary was the Holy Table, a slab of gold inlaid with precious stones, supported by four gold columns. Behind the altar, in the semicircular curve of the apse, were the seven seats of the priests and the throne of the Patriarch, all of gilded silver. Over the altar hung cone-shaped ciborium or canopy, with nielloed designs. Above the ciborium was a globe of solid gold, weighing 118 pounds, surmounted by a cross, inlaid with precious stones. The eucharistic vessels -chalices, patens, spoons, basins, ewers, fans- were all of solid gold set with precious stones and pearls, as were the candelabra and censurs.

Around the altar hung red curtains bearing woven figures of Christ, flanked by St. Paul, full of divine wisdom and St. Peter, the mighty doorkeeper of the gates of heaven. One holds a book filled with sacred words, and the other the form of the Cross on a staff of gold. On the borders of the curtain, Paul the Silentiary tells us, indescribable art has “figured the works of mercy of our city’s rulers”. Here one sees hospitals for the sick, there sacred churches, while on either side are displayed the miracles of Christ. On the other curtains you see the kings of the earth, on one side joined with their hands to those of the Virgin Mary, and on the other side to joined to those of Christ. All this design is cunningly wrought by the threads of the woof with the sheen of a golden wrap.

To the feeling of space and of regal splendor there was also joined the magnificent impression of light. If one entered St. Sophia by day the building seemed flooded by sunlight. Procopius tells us that the reflection of the sun from the marbles made one think that the building was not illuminated from without but that the light was created within the building. At night the thousands of oil lamps, all hung at different levels, gave the whole building a brilliant illumination without any shadows.

This effect of light had perhaps the highest effect on the worshipers. As Procopius puts it: “whenever anyone comes to the church to pray, he realizes at once that it is not by human power or skill, but by divine influence that this church has been so wonderfully built. His mind is lifted up on high to God, feeling that he cannot be far away but must love to dwell in this place he has chosen. And this does not happen only when one sees the church for the first time, but the same thing occurs to the visitor on each successive occasion, as if the sight were ever a new one. No one has ever had a surfeit of this spectacle, but when they are present in the building men rejoice in what they see, and when they are away from it, they take delight in talking about it”. Paul the Silentiary also tells us how that the Great Church, with its light shining through its windows at night, dominated the whole of Constantinople. The lighted building, he tells us, rising above the dark mass of the promontory, cheered the sailors who saw it from their ships in the Bosporus or the sea of Marmara.

It took five years to complete St. Sophia. Tradition has it that it took ten thousand workers, under the direction of one hundred foremen. Before it was completed, Justinian fixed the staff of the church at sixty priests, one hundred deacons, forty deaconesses, ninety subdeacons, and one hundred readers and twenty-five singers to assist in the services. There were also one hundred custodians and porters.

The story of the dedication of the church is that when the building was ready to be consecrated, the Emperor walked in procession from the gate of the palace across the Augustaeum to the outer doors of the church. Preceded by the Cross, Justinian and the patriarch then entered the vestibule. Then the Emperor passed into the building alone and walked to the pulpit, where he stretched his hands to heaven and cried, “Glory be to God, who has thought me worthy to finish this work! Solomon, I have surpassed thee!”