The Elder Joseph the Hesychast (+1959) Strugles, Experiences, Teachings (9)

15 Οκτωβρίου 2009

8. The Trials grow more Intense

Any extra aid from grace, when it comes legitimately to those who labour systematically, is like a prize, a good mark or a promotion, upon which the faith of contemplation increases perceptibly, according to the Fathers. And for beginners this is a sign of the bitterest struggle, while for those who are advanced it is an extension of illumination.

I used the word ‘systematically’, and with fear I shall explain in brief the difference this makes. The grace of God give help, comfort and consolation to all believers who live according to conscience. It gives to each according to what he requires to strengthen or console him. These gifts are exceptional, without repetition or continuation, and belong to the overall, general providence of God by which He sustains His creatures.

But to those who are sure in their faith, who for love of God and with certain faith in Him have rejected everything and denied even their nature, and exercise detailed vigilance to the strict keeping of His commandments – to these people divine providence does not appear exceptionally or in an undefined way, to offer some consolation or save them from some particular situation that befalls them. It attends them with a system of motherly guardianship, operating in a variety of ways. Through supranatural intervention, it manifests to them sensibly mysteries which are unknown and hidden, the wiles and ways of the demons and the mysteries of their nature and kingdom; it cures people of sicknesses, transports them great distances instantaneously, shows them various things from the past and future and – what is more – effects their spiritual progress. For those whom grace calls in the first rank, it becomes within them zeal and ardour and true piety. It strengthens them in ascetic labour generally and explains to them in detail the observance and meaning of the divine commandments, which is obedience to the divine will. Once they have achieved this much with its help, it then lifts them out of the unnatural, sinful life which they had been living, into the natural life in which they have ceased to disbelieve and disobey and sin. Then it gives them strength and help to weep and mourn for the guilty past. For their true repentance, it grants them forgiveness of the past and takes them on to divine illumination, having purified them in the course of their earlier struggle. Kept by grace in the requisite state of attention and appropriately trained and illumined, they attain to the stages of sanctification and to true humility, and ascribe everything to God and His Goodness, who condescends to call things that are not as beings (cf. 1 Cor. 1:28) and to grant salvation to man as a free gift.

In the Elder’s case, after this divine visitation the front opened up to a more bitter struggle, and the war became more intractable. Peace lasted a few days, then the war of the flesh redoubled. ‘I wept, I fasted to excess, I kept awake for ever longer, but the situation did not change. The attack would quieten down for a little while, but then it would start up again with fury. I would beat my body with sticks until I was black and blue from the waist down, but the war continued twice as fierce. My only consolation was tears and prayer, but I could see that the passion lived on and did not subside at all. Whenever grace shows its presence, then everything is bearable. But sometimes, for reasons that are purely providential, it withholds its presence and man loses hope; his fervour decreases, and even his faith is dulled. These are the hardest moments in spiritual life, because if God does not hold onto him here, man cannot endure. Again, when there are like minded and experienced brothers, they are a great help and it happens as the proverb says, “a brother helped by a brother is like a strong city” (Prov. 18:19). But what if instead of such brothers you have the opposite? When fellow monks who are irresponsible and, of course, ignorant of the situation, try to dishearten you with mockery and sarcasm, that is the worst thing that can happen. Because of my concern with the battles I was facing and my effort not to give ground in our order of stillness and in general to preserve our fervour, we restricted ourselves severely and went nowhere except to see our spiritual father. Our old clothes fell to pieces and we lived in great poverty, because we did not work either. At the monasteries they would give us things if we went there, but we avoided going, as I said, in order to maintain our estrangement and restraint in conversation; and so through deprivation we increased the war both within and without. Father Arsenios would go to the Lavra where they gave him some food, and that kept us going for the time being. But I was angry with myself, with Satan and with whatever else was prolonging this war for me. I constantly besought Christ and our most pure Lady, for whom I had from the beginning cherished a great devotion and love. “Lady, our Lady,” I would cry out in pain, “you that are the nurturer of virgins know that I have never inclined to carnal sin and, with the full knowledge of your Son, I have vowed complete chastity as far as is humanly possible. Why such violence and persistence? Is this going to overcome my will?”

‘So, sore burdened as I was, I went into my hut, shut the door and sat down on my stool in order to concentrate on the prayer, and gradually I began to calm down. Suddenly I heard a sound like the door opening, but I did not move because I said to myself, maybe it is Father Arsenios. But at once I felt in my lower members someone provoking me; I opened my eyes, and what should I see? The unclean spirit of fornication! He was just as our Fathers describe, with a bald, filthy head and little horns sticking up, a pale face, round red eyes full of wickedness, and his body filthy and covered with bristles like a wild boar’s! At once I flung myself on him with all my strength, but it was impossible to get a hold of him, naturally. There was only the feel on my hands of the roughness of his skin, and on my hands and all around his stench, like sulphur and slime, and he vanished. From that moment, by the grace of Christ and our most holy Lady, the weight of that war left me; the troubling thoughts ceased altogether and I felt like a small child, with no feeling of that passion. Then I sang hymns of victory and the ode of the prophet Moses, “the horse and his rider He has thrown into the sea” (Ex. 15:1). All night long I rejoiced and glorified our Christ, who did not despise my worthlessness and “who has not given us up as prey in the paths of our enemies” (Ps. 124:6, LXX).

‘Around dawn, when I sat down to sleep, God showed me the meaning of the struggle and war and in particular of the passions which fight against humans and enslave them. I dreamed that I was on quite a high point of ground, and opposite me I could see an immense plain, like a sea. A great throng of people, for the most part monks, were going across it from west to east. In front of them, over the whole extent of the plain, there were traps set. As they walked carelessly, they were getting caught in the traps; not all of them by the same part of the body, but some by the feet, some by the hands, some by the belly, some by the underbelly and, generally, the traps would catch them by all the different parts of the body, without exception. Once trapped, they seemed to wake up and began to weep so woefully that I too was weeping for sorrow. Then I saw this plain split down the middle, and as if from a crater there appeared a vile black ogre, very tall and full of fury, with his tongue hanging out, and he laughed in sarcastic satisfaction at the unfortunates who had been captured by his sorcery. Then I understood who he was and what he symbolised, and I groaned with pain: alas for our race because of this infernal serpent, who wars against us with such fury and persistence.’

* * *

The description given here of the life of the ever-memorable Elder will have irregularities in the sequence of events, in addition to its many deficiencies in language and syntax, because we never thought we would be writing this, and so never kept notes. Nor did he ever tell us his life story in a systematic fashion; but in his daily admonitions, as he advised us and strengthened us in our monastic life, at appropriate moments in our own struggles and perplexities he would tell us something of his own life, in corroboration of the scriptural or patristic text that he was quoting. At one time when I thought, just to myself, that I might write these things down, he realised what I was thinking and from then on avoided talking to us about them. It is quite possible, therefore, that we do not have events in precisely the right order. Our aim here is always to respect the humble mind of the Elder and to avoid any suspicion of making too much fuss, as some people might perhaps think. We have just one purpose in view: to encourage ourselves and others in the struggle that lies before us by the living example of contemporary warriors and, most of all, to share out as it were the ‘spoils’ of their experience, something that is of great importance amidst all the confusion of disorientation and ignorance which, unfortunately, is prevalent today. We recognise that there is nothing lacking in the biography or tradition of the Fathers so as to leave us with doubts or questions, nor can anyone imagine that they will be putting forward something new. On the contrary, it just serves as a confirmation of the Fathers’ advice. But the fact that the patristic way of life is revealed in practice and not just through stories of long-ago happenings gives great courage to those who are minded to take up the struggle. It is one thing to have the written word about far-off events centuries back in the past, and quite another to hear a contemporary or recent account which is verified by living people or things. Even though the methodology in our practical life is determined by the rules of life drawn up by our Fathers, there are many things which have today become inexplicable to our generation: some are considered excessive and unattainable, others unnecessary and irrelevant. But a living example gives assurance in every way. No one should ever imagine that he can describe the life of a spiritual person, however much he may have heard him or seen him or lived with him. A soul set on fire with divine love, a mind illumined with divine radiance and a body which has taken on to the full the marks of comprehensive self-denial and been dyed in the pain which strictness of conscience demands, and the fountains of his tears have become ‘meat and drink’ for him day and night – such a soul transcends natural laws and norms, and cannot be interpreted according to ordinary human criteria. And rightly does St Paul say that ‘the spiritual man judges all things, but is himself to be judged by no one’ (1 Cor. 2:15).

* * *

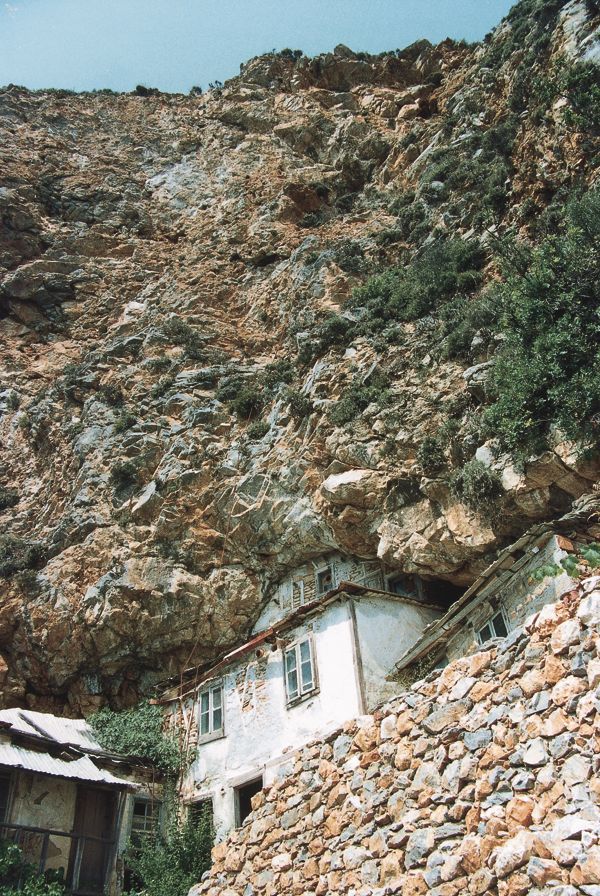

As divine grace and spiritual knowledge increased, through our Christ’s love for mankind and His divine aid, so the trials became harder. As he told us, ‘We decided to stay in our hut more and work at the enclosed life, something that had always appealed to me. So we thought that like the other Fathers we would procure some wheat, which they used to do in those days from the annual supplies of provisions during the summer. Every summer, boats belonging to the sketes would come to the various harbours and wharfs bringing various basic necessities in the way of food from outside Athos: the Fathers would then be informed, and would go down and take what each of them needed. The monasteries did not do this systematically, because they had their own dependencies from which they could bring in ready supplies all the year round. Father Arsenios and I went down to the harbour of Kerasia, which was nearest to the Skete below St Basil, to buy a little corn. We each took 25 okades (32 kilos) in our sacks, tied them on our backs at the custom is here and set off for the return journey. As it was our practice not to violate our regime, we were still keeping our fast, so as to eat at the ninth hour by Byzantine time, after Vespers. When we started up that steep hill with the sun nearly at its height, I found it difficult to keep going. My body was so worn-out and thin that I had difficulty walking unencumbered – how could I climb up such a hill with such a load, thirsty and on an empty stomach? I tried to go on a few times, but it was no good. “Arsenios,” I said, “I’m going to leave it here, and then we’ll go. I can’t carry on.” But I doubted whether I could manage it even without the load, because I felt totally faint with exhaustion. I stopped for a while and wept. “Lord, You know everything and can do everything,” I said; and immediately I felt consolation within me. I tied the load on my back again and told Father Arsenios we could go on. He gave me a strange look, and we set off in silence. For the whole journey, until we reached our hut, I felt someone behind me taking the weight of the load, and I was not carrying anything.’

When we felt faint-hearted he would tell us things like this, and what encouragement it gave us! There is another instance of the Elder’s self-denial that I want to relate to encourage those who are engaged in the struggle. This may seems incredible to those who are ignorant of the operation of divine zeal, what Abba Isaac calls ‘inebriation’, in those who have been found worthy to drink of this wine. All the saints described by St Paul became partakers of this inebriation, and they endured severe trials without a murmur. In particular the holy martyrs, drunk with this wine of divine love, endured the terrible martyrdoms ordered by the devil, which are horrifying even to hear of. The otherwise infirm nature of the human body, which has difficulty putting up with the heat of the sun in its mild form, endured searing fire in its entirety under the influence of this holy inebriation. Not to mention mutilation and the other tortures which the diabolical mind devised for an agonising death. And after the end of the persecutions during which the clouds of martyrs became drunk with desire for God and willingly sacrificed their members for the good confession, there continued the unbloody martyrdom of the unseen martyrs and confessors, the monks, from the moment when they felt the same fire as the martyrs of old. Silently, without any noise, they came out from the midst of the multitude and were separate; and not only did they touch nothing unclean (2 Cor. 6:17), but they did not touch even those needs and requirements which are natural and blameless. Alone with God alone who called them, they threw themselves into the struggle with the ancient serpent, and one by one they captured and overthrew his strongholds. Taking as their watchword the subjection of all their thoughts to obedience to Christ (cf. 2 Cor. 10:5), they suffered the complete martyrdom of the conscience, for the sake of which they endured and defied everything. Afflicted, destitute, persecuted, they passed their lives as sojourners in dens and caves and any kind of holes in the earth, out in the open and often up in the air, strangers and possessing nothing, not caring even for those mean needs of nature, they had only one aim: to love God totally (cf. Lk 10:27). Divine inebriation possessed them, and ‘the high praises of God were ever in their throats’ (Ps. 149:6).

With a complete denial of self, the very mention of which would make modern man turn away, they took up the cross of the all-embracing confession in order to reestablish in their entirety both covenants, that of baptism and that of their tonsure, and to enter with boldness with the Beloved into the inner shrine behind the veil (cf. Heb. 6:19), where He has entered as forerunner and granted us permanent and eternal deliverance. Given all this, who is able to describe these true athletes of the spirit, who have surpassed the bounds of our own power of vision?

* * *

Returning to our narrative, I want to relate the following incident in the Elder’s life. Towards the end of his life he allowed us to do certain things for him, because he was very strict with himself. Once when he had sweated very heavily he allowed me to wipe the sweat off his back with a towel. I then saw that there were scars on his body from wounds which had healed over, and as I knew he had never had any disease or injury, I asked him out of curiosity what the scars were. They were round, like the suckers on an octopus’s tentacles. Then he told us how it had happened. When they were at St Basil and he was forcing himself to the utmost in asceticism, he never changed his underclothes and especially not his vest; and because his constitution was not used to sweat and hardship, his back became covered with spots which caused him severe irritation. ‘But I didn’t take any notice, and when they troubled me too much, I pressed them by leaning against a wall. But they just got more inflamed and grew bigger and filled with matter. Then I took a big bag full of rusks from Iviron Monastery, which they had given us, and set out for our place. On the way the spots must have burst, because I could feel my vest sticking to my body, but again I didn’t take any care of them. I had learned to leave everything to God and our Lady, and gradually they healed, and the vest went into holes and that fell off too.’

We were shocked, however, and he said to us lightly, ‘The struggle against self-love is a hard one, but the grace of God does it all. If a person does not employ strictness, especially when he is starting out, then timidity and self-love take the wind out of his sails. And if a person does not enter upon the sea of trials with faith alone and without precautions, he will not discover perceptible aid from God and will never advance a single step. As the Holy Fathers tell us in their writings’ (he always meant Abba Isaac, whom he had as his inseparable companion) ‘if the intellect does not perceive divine help experientially, which is called “experience of divine aid”, it does not acquire self-denial; the excuses made by self-love lead it astray, and it wavers back and forth until gradually it ends up compromising. So do not be timid, especially now at the beginning when you are starting out, so that you may call forth divine grace. This grace is accustomed to console those who are sure in their faith, and those who, for love of God and for the sake of His commandment, throw themselves into the sea of self-denial. When at last the intellect is assured of the presence of help for those who believe, then it enters upon another kind of faith: not the introductory faith as in every believer, but the “faith of contemplation”, as the Fathers call it. This is the first stage, during which this person begins to be separate from the mass of people. If he does not bow to the mockery of the ignorant and lazy and turn to compromise, he then advances along the strait and narrow way of the confessors who are unseen and unknown to the mass of people (cf. Mt 10:32). Happy will he be if he has someone to guide him and support him and assure him that, by the grace of God, he is making progress. I did not have someone who understood me,’ he told us, ‘and I suffered greatly from the lack of faith that comes from ignorance, and in addition I had the reproaches and mockery of those who were always before me.’